In The Shadow of Slavery and Dirty Coal: How Daqo New Energy Became The World’s Lowest Cost Polysilicon Producer

Daqo New Energy (DQ) is the world’s lowest-cost producer of polysilicon, a feat we think has been achieved in part through the use of forced labor. It is currently worth $3 billion; we think in a year it could be worth 75% less.

The U.S. Department of Commerce added a Daqo subsidiary to an economic blacklist for “accepting or utilizing forced labor” in Xinjiang, thus banning the import of products to the U.S.

Subsequently, the U.S. passed the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, signed by President Biden this past December. This bill creates enormous revenue risks for Daqo, and there are indications the European Union may follow with import bans.

Daqo is headquartered in Shihezi, the “main base” of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corp (XPCC). The XPCC has been sanctioned by the Treasury for serious human rights abuses.

Daqo has denied any association with the XPCC. But the Chinese prospectus for Xinjiang Daqo states that “the company indicated that it has received subsidies for labor placements from the Chinese government.”

Daqo began production of polysilicon in Chongqing, but moved to Xinjiang in late 2012, citing XPCC-related benefits. Since then, Daqo’s average production costs have fallen by 50% and it’s production per employee is 3x higher than its next closest competitor.

We suspect there is an implicit quid pro quo with the XPCC that has allowed Daqo to lock in favorable prices on coal and other utilities, likely in exchange for their acceptance of forced-labor transfers.

Daqo is a favored holding of ESG funds, something we think they will have an increasingly hard time justifying. These funds should be embarrassed that they own it, as even cursory research shows it violates each pillar of ESG. Additionally, Daqo’s second-largest shareholder just finished a 5.5-year prison sentence for market manipulation.

Daqo is a commodity producer operating in a boom/bust end market that is about to be flooded with supply. Daqo benefited tremendously from several outside factors that helped push the price of polysilicon up nearly 500% over the last year. But now we think we’ll get to see operating leverage work in reverse.

Disclosure: We are short shares of both Daqo New Energy and Jinko Solar.

Of the major publicly traded polysilicon producers, Daqo has operating margins that are nearly twice as high as other competitors.

Source: Bloomberg, Company filings

Daqo has become one of the largest and lowest cost producers of polysilicon in the world. Daqo is an extreme outlier compared to other polysilicon producers, generating nearly 3x more metric tons of polysilicon production per employee.

We find it extremely suspicious that a company accused by many governments of using forced labor just so happens to be 3x more efficient on a production per employee basis. The simplest explanation is usually the correct one.

Source: Bloomberg, Company filings

Introduction

In western China, Daqo New Energy (DQ) has done something no polysilicon producer has ever been able to do: manufacture polysilicon for less than $5 per kilogram. This cost has fallen 50% since its move from Chongqing to Xinjiang in late 2012, making it the world’s lowest-cost polysilicon producer that sells polysilicon to almost every solar panel producer. The production of polysilicon begins by processing quartz into metallurgical grade silicon. In the next step, it is subjected to extremely high heat which purifies the product into industrial grade polysilicon. The process is enormously energy-intensive, which makes Xinjiang’s vast coal resources an ideal energy source.

The three cost inputs to polysilicon production are energy, labor, and raw material costs. We know for sure that Daqo has locked in low rates on coal prices through sweetheart deals with the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC), a “paramilitary” organization that stands accused of crimes against humanity. Yet Daqo management has repeatedly claimed to have no association to the XPCC to the U.S. press.

The U.S. just passed a bipartisan bill effectively banning the import of products from Xinjiang, in turn creating a huge revenue risk for the company. A short term boom in polysilicon prices, the artificial economics of the business, and the continued support of ESG funds have helped propel Daqo from what was historically a sub-$200 million market cap company to a $3 billion market cap today.

Over the last year, there has been a massive increase in the scrutiny of labor issues and abuses in Xinjiang. Daqo began commercial operations in Chongqing in 2008, but its business would not improve until its move to the XPCC city of Shihezi in Xinjiang in late 2012. At the time of the move, Daqo cited lower labor and energy costs as key factors for moving. In 2020 the XPCC was sanctioned for “perpetrating a cultural and demographic genocide against ethnic minorities.” It also controls the energy grid in Daqo’s headquarters, something Daqo has cited as a contributing factor to its claimed status as the lowest cost polysilicon producer.

Source: New York Times, Bloomberg

Daqo’s CEO has claimed that there is “absolutely no” connection between the XPCC and Daqo, but there is clear evidence that the entities are inextricably linked. After its move to Shihezi, the home-base of the XPCC, Daqo would begin to see costs fall and benefit from what seems to be quid pro quo deals with the XPCC.

The price of polysilicon is up almost 500% over the last year as several suppliers were forced to halt production. But there is a massive amount of production that has already been coming online, and we think the price of polysilicon, historically subject to massive boom bust cycles driven by over and under supply, will moderate. Daqo is massively exposed to price declines, and we think profits could plunge as much as 75% as operating leverage works in reverse. For example, a previous 20% decline in polysilicon average selling prices (ASP) led to a 60% decline in gross profits. We think there is a significant risk to both revenues and margins as customers ditch Daqo. We could see profits plunge by 80-90% under several paths.

JinkoSolar (JKS),Daqo’s second largest customer, is in the business of purchasing polysilicon and turning it into solar modules. Jinko has its own ties to forced labor - it previously invested CNY3 billion in the Xinyan Industrial Park 237, which houses the Jinko Solar factory complex as well as a high-security prison and an internment camp. Satellite images suggest that as Jinko was building its factory, the detention facility was being built in the same industrial park.

We think the ESG funds that hold Daqo and Jinko - many of which have made statements that seem to disallow the holding of these companies - will be forced to sell. Solar shipments with provenance in Xinjiang are being stopped at the border. We think there is evidence that global purchasers have been shying away from purchasing Xinjiang-based suppliers for fear that deliveries will be held up. On top of that, there are massive supply increases of polysilicon production that we think will cause the price of polysilicon to fall, mirroring a historical boom/bust pattern in polysilicon prices. Due to the nature of its business, falling polysilicon prices are especially bad for Daqo.

Daqo and Jinko are vastly different businesses, but we think similar arguments can be made for selling or shorting shares of each company. We are short shares of both Daqo New Energy and Jinko Solar. Sunshine is the best disinfectant, and the bright light of hundreds of think tanks, investigators, and global governments has been shining on Xinjiang.

Clear Evidence That Daqo and Jinko Are Using Forced Labor

Xinjiang is an inland Chinese territory that holds the vast majority of energy resources in China; almost 40% of the coal, 20% of the oil, and 20% of wind energy deposits of China are in Xinjiang.

It is also home to the Uyghurs, a Turkic ethnic minority group that have long lived in Western China. According to a recent Congressional report,“As many as 1.8 million Uyghurs, ethnic Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and other Muslim minorities are, or have been, arbitrarily detained in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). The severe human rights abuses, torture, political indoctrination, forced renunciations of faith, and widespread and systematic forced labor occurring in mass internment camps may constitute crimes against humanity under international law.”

International trade journal Foreign Policy discussed some of the history of the XPCC from 2014.

“The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC), known as the Bingtuan in Chinese, was established by then-Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong in 1954 with a mandate to stabilize the volatile Xinjiang region abutting Central Asia…”

The history of the Uyghur crisis is a long and interesting one; the geopolitical history of Xinjiang is a long one: originally standing as the Islamic Republic of East Turkistan in 1933. What followed was a period of ownership exchanges between the Soviet Union and China, until the Uyghur-majority region finalized itself in the area known as Xinjiang. Starting in the 1950s, China saw the opportunity to dilute the presence of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang through the encouraged migration of the Han Chinese, the major ethnic group native to China. And it worked…

In 1945, Han Chinese comprised only 6.2% of the Xinjiang population… but by 2008 Han Chinese made up 40% of the region, turning the Uyghurs into a minority population in what was their ancestral home.

As Han Chinese made up more and more of the population, high-quality jobs and government support for the Uyghurs slowly diminished in tandem. The situation has always been tenuous and fraught with conflict, but by the late 2000's cases of violence had become more frequent. In 2009 a Uyghur protest against the discrimination they faced from the Han Chinese and CCP erupted in a sea of violence. About 200 people were killed and hundreds more were injured during the riots. This event served as a catalyst for China’s crackdown upon the Uyghur population, utilizing the event as a citation for calling the Uyghurs “terrorists” and hyping up the “danger” they pose to the CCP’s prosperity.

A white paper authored by the XPCC itself admits as much, claiming that it “played a crucial role in fighting terrorism.” To do this it has created an enormous network of prisons used to enslave Uyghurs, an ethnic minority, under the guise of “re-education” and “social literacy.”

According to the Human Rights Watch,“In May 2014, the Chinese government launched the “Strike Hard Campaign against Violent Terrorism” (严厉打击暴力恐怖活动专项行动) in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang or XUAR) against Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims.” Daqo and Jinko have directly benefited from these campaigns against Uyghurs.

The abundance of cheap coal and forced labor in Xinjiang would transform the polysilicon market. By 2020, 45% of the global polysilicon supply was coming from this “Uyghur region” in inland China.

Source: In Broad Daylight: Uyghur Forced Labour and Global Solar Supply Chains

The conversation about forced labor, percolating in the background for many, finally hit the front page of the newspaper in January 2021 when the New York Times published an article titled “Chinese Solar Companies Tied To Use of Forced Labor.”

“Major solar companies including GCL-Poly, East Hope Group, Daqo New Energy, Xinte Energy and Jinko Solar are named in the report as bearing signs of using some forced labor, according to Horizon Advisory, which specializes in Chinese-language research. Though many details remain unclear, those signs include accepting workers transferred with the help of the Chinese government from certain parts of Xinjiang, and having laborers undergo “military-style” training that may be aimed at instilling loyalty to China and the Communist Party.”

More importantly, the situation has been escalating politically. The U.S. Department of Commerce added Daqo, along with several of its suppliers, to an “entity list” effectively blacklisting the companies and banning the import of products on this list from import into the U.S.

“The Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) added five Chinese entities to the Entity List for accepting or utilizing forced labor in the implementation of the People’s Republic of China’s campaign of repression against Muslim minority groups in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). This action targets these entities’ ability to access commodities, software, and technology subject to the Export Administration Regulations (EAR), and is part of a U.S. Government-wide effort to take strong action against China’s ongoing campaign of repression against Muslim minority groups in the XUAR.”

The June 2021 release named Xinjiang Daqo New Energy Co. Ltd., and Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps. (XPCC), as well as three other Xinjiang-based entities that were accused of using forced labor.

In July 2021, the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Department of Treasury, the U.S. Department of Commerce, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, and the U.S. Department of Labor issued an “Updated Xinjiang Supply Chain Business Advisory.”

The report revealed a number of human rights violations occurring at these camps, including sleep deprivation, medical neglect, torture, forced labor, forced ingestion of unidentified drugs, forced sterilizations and abortions, sexual abuse, rape, and many more horrific acts. The report claimed to find “insurmountable evidence indicating forced labor is used at nearly every step of the solar production process.”

Images of the living quarters inside a Uyghur “vocational training center”

Source: BBC

The U.S. government’s response contains further information on the state of forced labor in Xinjiang and the effects it has on several other industries. We have linked a copy here for those interested in reading further. For the more visual learners, here is some drone footage from 2019 allegedly showing one of these “labor transfers.”

The Political Temperature On Xinjiang Is Heating Up

On December 6th, the U.S. formally announced its diplomatic boycott of Beijing Winter Olympics over human rights abuses occurring in Xinjiang. White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki stated, “U.S. diplomatic or official representation would treat these games as business as usual in the face of the PRC’s egregious human rights abuses and atrocities in Xinjiang and we simply can’t do that.”

Just two days later, on Wednesday, December 8th, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison said that Australia will join the U.S. in a diplomatic boycott, citing “human rights abuses” in Xinjiang along with “many other issues that Australia has consistently raised.”

U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson also announced that the U.K. will be boycotting the Olympics, also due to the human rights abuses in Xinjiang. Canada would follow suit the next day.

The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act

On Wednesday, December 8th, the House voted 428-1 in favor of passing the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, which “imposes various restrictions related to China's Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous region, including by prohibiting certain imports from Xinjiang and imposing sanctions on those responsible for human rights violations there."

The House also passed a resolution on Wednesday in a similar 427-1 vote which states “the Chinese government is responsible for ongoing abuses against the Uyghurs and other ethnic and religious minority groups” and condemns the ongoing “genocide and crimes against humanity.”

On Friday, December 10th, the United Nations’ rights office disseminated its plan to soon publish findings on abuses in Xinjiang. A spokesperson cited “deeply disturbing” information on Xinjiang and pointed to “patterns of unlawful detentions and coercive labor.”

There is also the very real possibility that the EU will follow suit on import restrictions, with the German Foreign Minister recently demanding a ban on goods with links to forced labor.

Daqo’s Business Would Improve Dramatically After Moving To An XPCC-Administered City In 2012

Daqo began producing polysilicon in 2008 in Chongqing, but business would not become lucrative financially until 2012 when the company moved to Shihezi in Xinjiang, the home base of the XPCC. Justifying the move, Daqo cited lower costs of doing business in the region.

“We now focus on our operations in Xinjiang in northwestern China. The cost of doing business in western China is generally lower than the coastal areas.” - Daqo Annual Report, 2013

Ten years later, it seems these lower costs came in the form of forced labor of Uyghurs, an ethnic minority in western China.

As early as October 2010 Daqo was announcing plans to begin construction of its Phase 2 facilities in Xinjiang. Part of the $80 million Daqo raised in its October 2010 IPO would be invested in building these Xinjiang facilities. Daqo’s move to Xinjiang would have massive consequences for Daqo’s business. Here’s how a “generally lower” cost of doing business has impacted Daqo financials:

Source: Bloomberg

For a commodity producer operating in an unstable end market, the improvement in return on equity has been impossible to miss since the move to Shihezi. It was further boosted in 2021 as the price of polysilicon rose nearly 500%. We think this is peak return on equity for the polysilicon cohort, as things will likely never be this good.

But nowhere is the massive change more clear than in Daqo’s reported production cash costs. Daqo’s average polysilicon production cash cost fell from $12 per kilogram in Q1 2014 to under $6 per kilogram in Q1 2021. For a commodity company to become 50% more efficient in what it costs you to get the product out of the ground is truly stunning.

Source: Company filings

It is worth paying attention to outliers. There was a famous fraud called Longtop Financial, one of the first Chinese reverse merger frauds to be exposed. The “tell” of the fraud was gross margins that stood out far in excess of other software companies. At the time Citron noted: “If the China space has taught us anything, it is that when something seems too good to be true, it probably is.”

Daqo uses the same production processes as other polysilicon producers, and while yes, there could be some variance (as there is between Xinte Energy and Wacker) due to technical aptitude, it seems highly unlikely that that is the entirety of the explanation.

The comparison to Longtop is apt for other reasons. Longtop and Daqo share an auditor: Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu. The same auditor sued for missing a $7.4 billion fraud in 2011. More recently, it served as the auditor of GSX TechEdu (GSX) now known as Gaotu Techedu (GOTU). GOTU is a chinese ed-tech company that has come under fraud allegations and seen its share price fall 98% over the last twelve months.

Forced Labor On Both Sides Of The Supply Chain: From Suppliers to Customers Puts Daqo In A Precarious Spot

Daqo seems to have exposure to forced labor on both sides of its supply chain. The vast majority of its raw materials come from two companies: Hoshine and Sokos.

According to the Xinjiang Daqo prospectus, Sokos supplies 47% of Daqo’s raw materials purchases.

From the “In Broad Daylight” report:

“State media reports announced that Sokesi also participates in the state-sponsored “organised transfer of labour from poor families in ten deeply impoverished counties in the three prefectures of southern Xinjiang.” The labourers work in Sokesi’s facilities in the Changji High-tech Zone within the Zhundong Economic and Technological Development Zone, which “transferred” more than 700 labourers from Hotan through “surplus labour” programmes in March 2020 alone. State media reported Sokesi would sign three-year contracts for surplus labourers in 2020. There is not much more information about Sokesi accessible in publicly available documents.”

Daqo’s second-largest supplier also has ties to the XPCC:

“Xinjiang Hoshine is exposed to labour transfers through its chemicals supplier Xinjiang Tianye Co., Ltd. Xinjiang Tianye is a state-owned enterprise of the 8th Division of the XPCC. Xinjiang Tianye’s 2018 annual report indicates participation in a wide array of so called poverty alleviation programmes, including labour transfers and vocational training programmes. The company reports that it has “absorbed” (吸纳) 100 local workers, which typically is a euphemism for labour transfers. Furthermore, a state media report in 2020 provides evidence that the company has been the recipient of “poverty alleviation” surplus labour transfers as a “paired poverty alleviation work unit” (对口帮扶单位). It may be that Tianye primarily supplies Hoshine’s downstream sealant projects and not their metallurgical-grade silicon projects; nonetheless, this again raises the likelihood of labour transfers in Hoshine’s supply chain.

Source: In Broad Daylight

Daqo’s own filings make it clear they are in Xinjiang not only because of cheap labor, but also because of cheap suppliers, cheap in part because of their use of forced labor.

“Our polysilicon manufacturing facilities are located in Xinjiang to be close to sources of raw materials and energy for polysilicon production. We do not tolerate any use of forced labor whether in our own manufacturing facilities or, to the best of our knowledge, throughout our supply chain. However, we cannot assure you that the relevant U.S. authorities will not decide that forced labor exists in our supply chain or in the manufacturing of our polysilicon and, pursuant to Section 307, prohibit U.S. imports of products (including those of our customers) containing our polysilicon.”

And yet, Daqo’s CEO continues to play dumb when asked about the government’s treatment of Uyghur’s, saying “Do they exist or not? Actually, I don’t know.” He would go on to say “certainly if they do exist, I think there are moral standards that this will be judged against.”

He doesn’t need to look far for evidence. There is clear evidence of forced labor both among key suppliers and key customers. Additionally, it is clear that Daqo management has been lying to the U.S. press about its XPCC connections.

Saying you’re not associated with them to the press and admitting you have a key cost advantage due to the XPCC’s managing of the electrical grid is an unequivocal lie.

An April 2020 article published in a local state-operated paper proves at least some money has flowed from the XPCC to Daqo. The article stated that a company called Xinjiang Daxin Energy had received a “corporate social security subsidy” of nearly 490,000 yuan.

Xinjiang Daxin Energy is one of three aliases listed for Daqo by the Department of Commerce.

Daqo is in a tricky spot. If it distances itself too much from the XPCC, it risks running afoul of local officials and the spigot of support being turned off. Yet globally it must appear that it has distance from the paramilitary organization linked to crimes against humanity, for reasons that, we hope, are self explanatory.

Daqo CFO: “Good Chance” Xinjiang Polysilicon is banned by the US; Could the EU follow?

This is a known issue in the industry, and it seems that some firms have taken the opportunity to distance themselves from Xinjiang polysilicon. Daqo is clearly aware of the issue and has arranged factory tours for U.S. journalists and analysts; one Bloomberg headline suggested it was trying to “Woo the West.” Yet it appears there is already a movement on the margins away from Xinjiang polysilicon, as reported by Bloomberg.

“Many developers have already been moving away from Xinjiang-based polysilicon, and indeed, such decisions have contributed to the supply squeeze and price increases within the solar industry during the first half of 2021.” - Level Ten Energy June 2021

Daqo’s own CFO admitted that there was a “good chance” that the U.S. would ban polysilicon with provenance in Xinjiang, which would suggest that any Daqo customers that generate revenue in the United States might think twice about purchasing from the company currently, for fear their product will be held up at the border or not allowed entry into the United States.

“Daqo’s chief financial officer, Ming Yang, acknowledges there’s a “good probability” that Xinjiang-made polysilicon will be banned by President Joe Biden.”

These sanctions are not just academic in nature. They are causing products to be held up at the border and there is speculation that this has caused order books to shift to non-Xinjiang polysilicon. There is real-world evidence that these regulatory interventions are having an economic impact on the companies. An article in the Wall Street Journal states, “Companies whose shipments have been seized will have to provide proof showing the absence of forced labor, or that forced labor conditions have been mitigated, through documentation such as payroll records and third-party audits.”

“China’s JinkoSolar Says Some Panels Being Held At U.S. Border”

That was a Reuters headline from September 2021 highlighting Jinkos’s disclosures on some of the issues with its product being held up at the border. On the second-quarter conference call, Goldman Sachs analyst Brian Lee would press the company.

Source: Jinko earnings call transcript

While Jinko is trying to shy away from disclosing the extent of the problem, we believe that there will be shifts in purchasing patterns away from companies with Xinjiang exposure. This is a pattern that seems to already be in motion. A recent report suggested that 72% of the new polysilicon expansion is happening outside of Xinjiang, and also notes the sheer size of the new production that is about to come online.

“Sizeable pipelines for new polysilicon expansions continue to be built with over 1.2 million tons expected to be online by 2023. Although the majority of expansions (72%) are planned for outside of Xinjiang.”

A one-two punch of falling polysilicon prices, as well as revenue impact from polysilicon purchasers shying away from polysilicon from Xinjiang, would have devastating consequences. Alternatively, if Daqo attempts the long and arduous route of entirely shifting its manufacturing footprint and exposing itself to market rates, margins would take a massive hit.

Jinko Has A Prison Facility On Its Corporate Campus

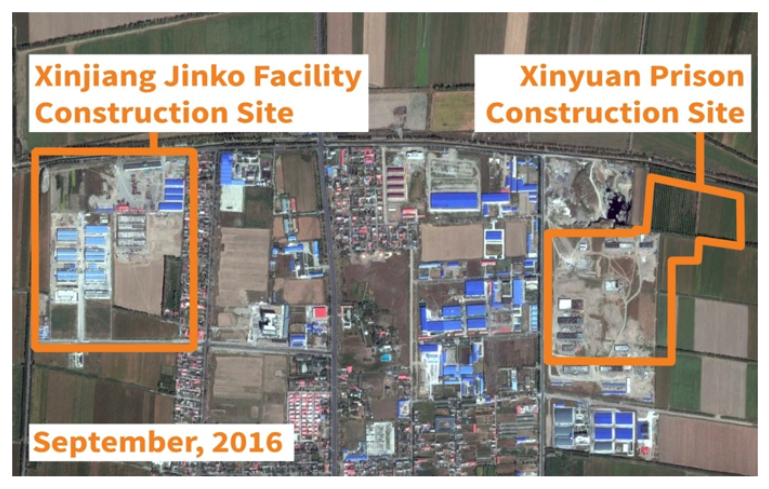

Satellite images of the Xinyuan Industrial Park taken over a five-year span further support the case of the use of Uyghur labor at Jinko.

Source: Xinyuan Investment Guide

The schematic above, taken from the Xinyuan Investment Guide, provides a detailed map of an area in which Jinko facilities reside today. The pink rectangles on the left designate Jinko Solar facilities. The large green rectangle in the top right designates 新源监 狱 (“Xinyuan Prison'').

The East Turkistan National Awakening Movement (ETNAM), an Uyghur human rights advocacy group, and the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), an independent, non-partisan think tank, have identified the Xinyuan Prison as an Uyghur-designated concentration camp and prison.

The satellite image below shows where these planned locations will break ground shortly in the future.

Source: Google Earth, CNES / Airbus, ETNAM, Bloomberg, Bleecker Street Research

Here, construction of the facilities can be seen as the park begins to break ground.

Source: Google Earth, CNES / Airbus, ETNAM, Bloomberg, Bleecker Street Research

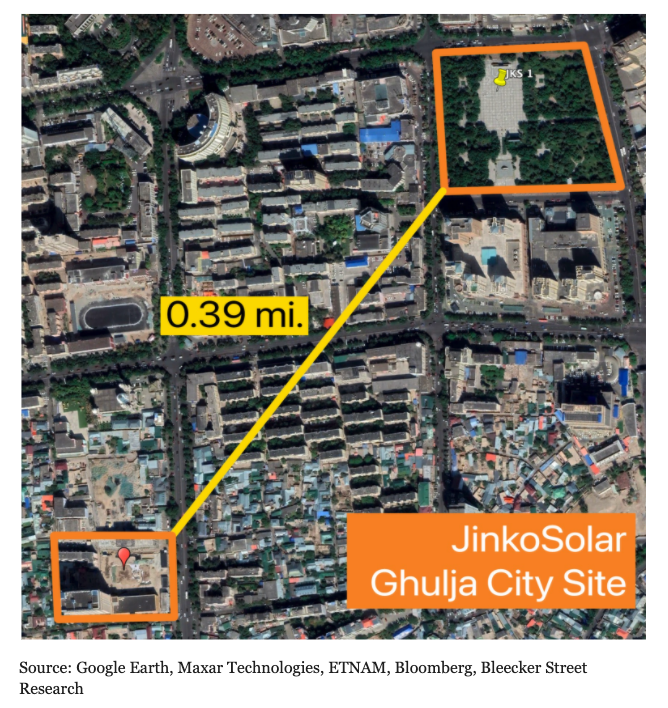

Finally, a recent satellite image displays a large Jinko Facility on the left with a fenced-in prison complex on the right. These facilities sit less than a mile away from one another.

Source: Google Earth, CNES / Airbus, ETNAM, Bloomberg, Bleecker Street Research

Jinko Acceptance of “Labor Transfers”

In April 2020, a government-operated local newspaper from the Xinjiang region reported that Jinko Solar’s Xinjiang facility has accepted 78 “registered unemployed personnel” from Xinyuan/Künas County – an area in the XUAR well-recognized to contain a large Uyghur population.

This phrase is often used in what the CCP dubs “labor transfers” and “poverty alleviation” schemes. Several human/Uyghur rights organizations, media outlets, and research organizations including the New York Times, Washington Post, ASPI, RFA, and CSIS have identified these processes as methods in which Uyghurs are essentially forced out of their homes and into these prisons.

This newspaper article provides a table listing these 78 individuals’ names (many clearly of Uyghur origin) and education levels. All of these individuals are reported to have been given a state subsidy of 1,000 CNY (~$158 USD at the time) to work at the Jinko facility.

In July 2020, the same newspaper would go on the report an additional batch of “40 new employees from poor laborers in southern Xinjiang.”

Source: Xinyuan Government Newspaper

Another Chinese media report states that 54% of employees at Jinko's Xinjiang facility are "ethnic minorities," including "former farmers and herdsmen" (a very common occupation of Uyghurs).

Jinko isn’t alone in these “labor transfers.” In a prospectus published on the Shanghai Stock Exchange’s website for Xinjiang Daqo, a Daqo New Energy subsidiary, the company’s “labor placement subsidies” are disclosed. We have linked a copy of the prospectus (only available in Chinese) here.

Daqo’s Exposure To Jinko:

Jinko has long been one of Daqo’s largest revenue sources, historically accounting for 15-25% of Daqo revenue.

While Daqo’s polysilicon sales primarily occur in mainland China, its clientele maintains a large international customer base. Jinko in particular generates 28.7% of its revenue from the United States and only 17.0% from Mainland China; along with a large amount from other western countries. For a downside case, we’d point you back to Daqo’s CFO suggestion there is a “good chance” that the U.S. bans Xinjiang polysilicon. If the EU followed, Jinko could lose nearly 50% of its revenue.

Source: Factset

Operating Leverage In Reverse Is a Bitch; What Happens To Daqo When Revenues Decline Ever So Slightly

As a commodity producer, Daqo’s financials are very closely linked to the price of polysilicon. If and when polysilicon prices decline, it could be a disaster for Daqo financially. If there are global sanctions against Daqo, it could be much, much worse. We don’t need to speculate though, the damage that could happen is already visible in Daqo financials.

Let’s look at what happened early during the pandemic. In Q1 2020 Daqo generated $169 million in revenue and $57 million in gross profit. In Q2 2020 Daqo generated $134 million in revenue, a decline of 21%. This 21% decline led to gross profit falling 60%, to $23 million. This was in part due to COVID issues, but also because Daqo saw polysilicon ASPs fall by 20%.

The last time Daqo saw a sequential ASP decline of 20%, profits fell 60%. If polysilicon prices revert to 2019 levels after the onslaught of supply that is inbound, Daqo could reasonably see profits fall 90%.

Source: Company filings

Polysilicon Is A Boom/Bust Commodity, And Evidence Points To It Being On The Cusp Of A Bust

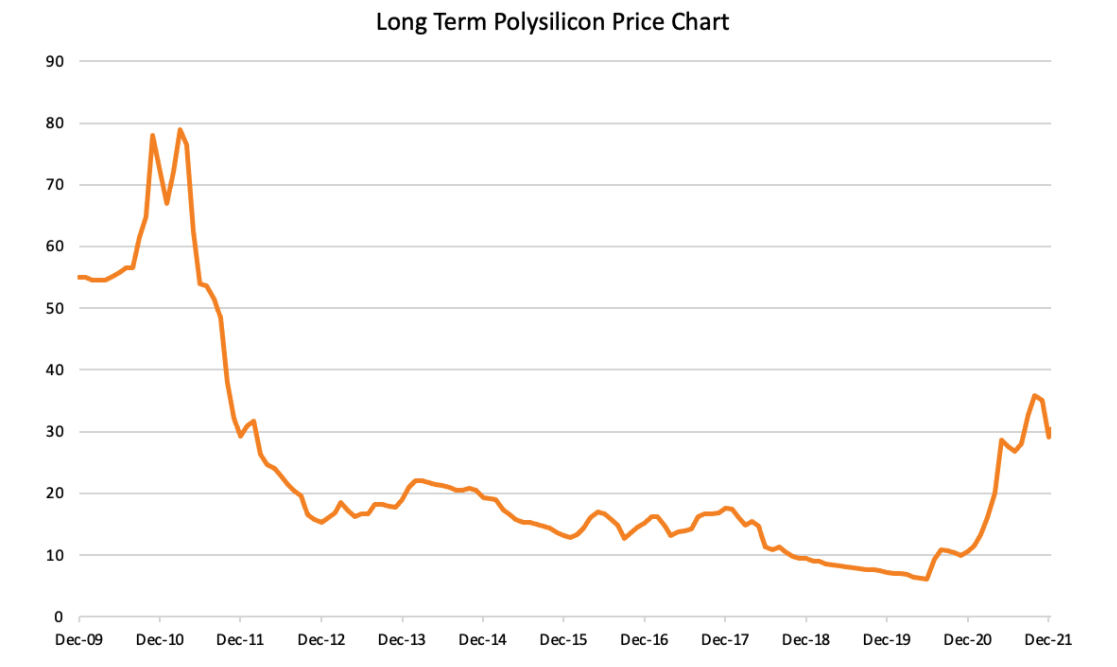

Polysilicon is a commodity. Like all commodities, the industry has historically been subject to boom/bust cycles. Initially a commodity that fed the semiconductor industry, polysilicon has historically been subject to massive price swings caused by oversupply and shortages. As the solar industry began to warm up in the early 2000's, solar manufacturers transformed the market causing a temporary boom in polysilicon prices from 2001 to 2008. Eventually new market entrants (including Daqo) would bring new supply to market, driving down polysilicon prices for much of the 2010s. But last year, several short term factors would come together to take supply off the market. Much is about to be added however, and we think Daqo is experiencing peak financial results.

From 1981 to 2008 the price of silicon was highly cyclical, following a pretty clearly defined eight-year boom/bust cycle. Over this period the primary source of demand for polysilicon was the semiconductor industry, an infamously cyclical industry. The chart below from Bernreuter Research highlights the boom/bust nature of polysilicon.

Source: Bernreuter Research

In the early 2000’s a burgeoning solar industry caused a massive demand shift and ensuing price bubble as solar producers all rushed to try and secure polysilicon supply, anticipating future demand.

Increasing Solar Demand For Polysilicon Causes Massive Use-Shift:

Source: Bernreuter Research

Polysilicon prices would surge from under $40 per kilogram in January 2004 to $460 per kilogram in January 2008. But massive supply increases, lower demand from the financial crisis, and massive increases in supply would cause prices to fall drastically and continue to fall most of the decade.

Source: Bloomberg

A number of factors came together to cause the price of polysilicon to rise drastically. We view this as something that will rapidly reverse, in part due to the massive amounts of supply that are about to come online from nearly every major polysilicon producer. A move toward vertical integration by panel manufacturers will reduce the reliance on Chinese producers. In addition to high prices eliciting a supply response, they have pressured the economics of solar developers, crimping demand. Polysilicon has historically been a boom-bust commodity, and we think it will be a severely oversupplied market in the near future.

Source: Bloomberg

Given the inherent leverage in its business model to the price of polysilicon, this move was massively beneficial for Daqo financials.

We think this move upward was the result of a number of freak accidents. For example, a large polysilicon plant was taken offline due to a Chinese flood, production that is now coming back online.

In November, a JP Morgan analyst noted that “polysilicon tightness is short-lived,” and that they “expect polysilicon supply will increase by more than 35% in 2022.” JPMorgan also noted that their covered solar stocks are trading 2.5 standard deviations above average. In justifying their price target, they noted that Daqo would have “no growth” in 2022 and 2023.

There’s already evidence that the oncoming supply is dampening prices, which would hurt Daqo.

“Prices have already come off 17% since November after Tongwei Co., Daqo New Energy Inc. and GCL-Poly Energy Holdings Ltd. - among the key global producers - opened new plants or lines with combined capacity of 160,000 tons a year, adding to a current global fleet of about 620,000 tons, according to BloombergNEF data. Another 550,000 tons of capacity is under construction, most of which will be online by the end of this year.”

Daqo is a cyclical company and investors should remember operating leverage works both ways.

Daqo’s Second Largest Shareholder Just Got Done Serving 5.5 Years In Prison for Market Manipulation

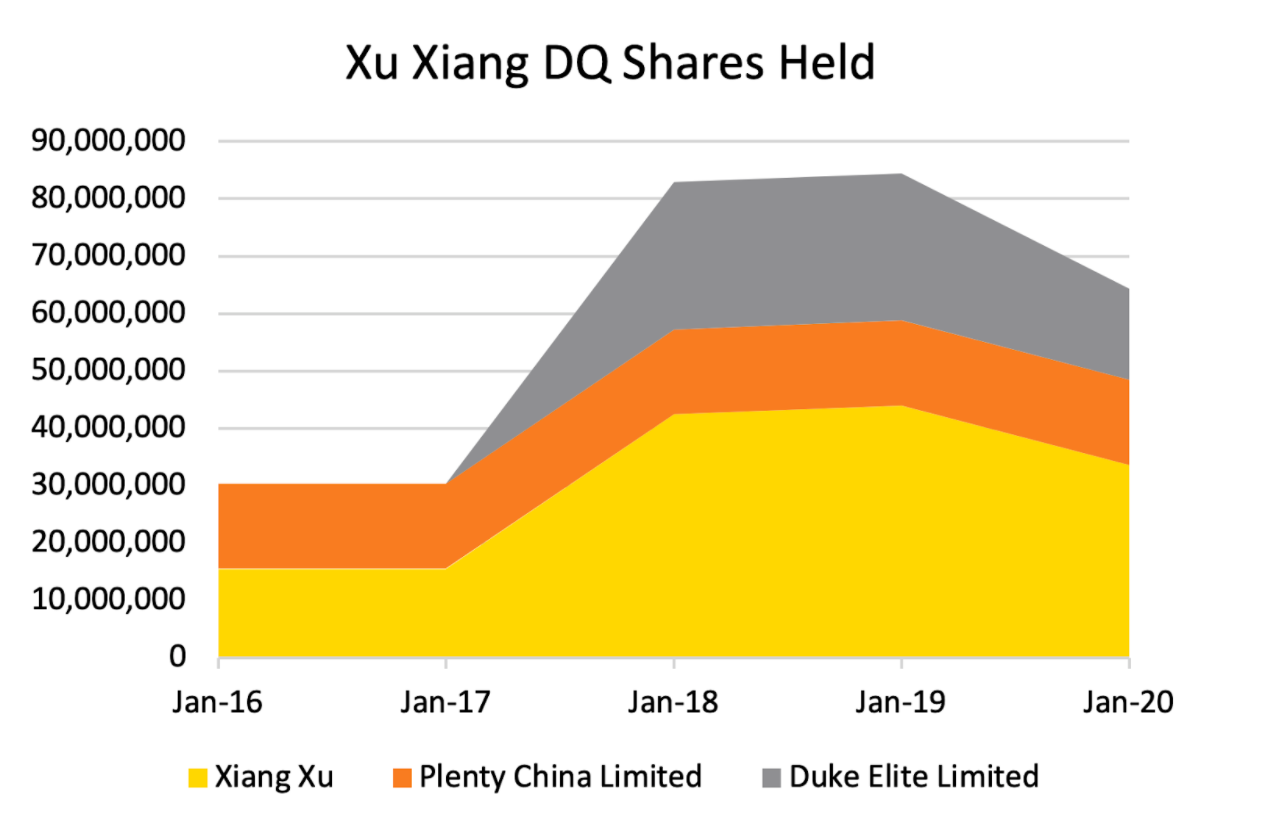

While ESG funds might be responsible for the last wave of volume, Daqo investors should be aware of who the longtime and second-largest Daqo shareholder is.

In late 2010 an investor named Xu Xiang, investing through an entity called Plenty China Ltd, purchased 8.8% of the float of Daqo. Over the next 9 years, entities related to Xu Xiang would go on to control almost 90 million shares. Daqo’s stock chart looks very similar to many of the Archegos-related blow-ups that happened in 2021.

Source: 13G filings

Xu Xiang was once a rising star hedge fund manager in China before being sentenced to 5.5 years in prison on charges of market manipulation after an April 2016 arrest.

Source: South China Morning Post

Xu would be released from prison in July 2021, around the time he, Plenty China Ltd. and Duke Elite Ltd. began selling Daqo shares.

Yet what concerns us more is the fact that a large part of Daqo’s recent run-up is related to the massive inflows into ESG funds. ESG funds have no business owning either Daqo or Jinko, for reasons we hope to be clear. Yet they do, and Daqo’s chart reminds us of many of the stocks that were linked to the blowup of Archegos.

Daqo and JKS are violators of every single “ESG” metric. Many of the funds that own Daqo and JKS are making public claims that would seem to preclude them from investing in companies with links to forced labor. Do you want to own companies profiting from forced labor?

Over the last decade investors have poured into “ESG” funds, that claim to invest and promote companies that are good for the environment, have a positive social impact, and exhibit good corporate governance. We view Daqo and its third-largest customer, JKS, as violators of every single “ESG” metric. Funds that have helped propel Daqo into what at its peak was a $10 billion + market cap make public claims that are directly contradicted by what is happening at Daqo. We call on these funds to at least explain what the hell they are doing by owning these companies.

The total AUM of the ESG ETF space has risen from under $10 billion in 2014 to nearly $200 billion at the end of 2020. The best performing of these ETFs was the Invesco Solar ETF (TAN), the fourth largest shareholder of Daqo, owning about $110 million worth of stock.

Invesco markets the ETF to investors by saying:

“For many investors, ESG (environment, social, and governance) considerations are important factors when it comes to evaluating potential investments. By selecting ETFs with strategies that align with their own values, investors can gain exposure to dynamic sectors of the 21st century economy while also investing in a brighter tomorrow.”

Invesco is hardly the only offender. Key shareholders of Daqo and JKS make claims about their product that seem directly contradicted by statements from their official statements and policies on human rights, management commentary, and research publications.

Let’s try and envision a world in which ESG funds dump Daqo and Xiang Xu continues to sell. Daqo’s share price would fall and cost of capital go up, and who would be the marginal buyer of this kind of security? Perhaps Chamath who recently claimed to not care about the situation on a podcast, prompting the Warriors to issue a statement claiming he doesn’t speak for them.

How Daqo and JKS Violate Every ESG Metric:

Environmental: While solar panels are in theory a low-carbon purchase/investment, the making of them isn’t necessarily the cleanest. A June 2021 article in the Wall Street Journal provided some prescient quotes about the industry; quoting Robbie Andrew from the Center for International Climate Research as saying, “if China didn’t have access to coal, then solar power wouldn’t be cheap right now.” One quote in particular stood out to us as a potential issue, citing shifting demand to low-carbon panels: “some Chinese polysilicon producers are well-placed to respond to Western demand for low-carbon panels. Tongwei, the world’s largest producer, has some factories that run on hydropower. However, Daqo New Energy and GCL Poly, Tongwei’s main Chinese competitors, rely overwhelmingly on coal, according to the companies.”

Social: One would hope this is fairly self-explanatory by now.

JKS Governance: In a series of reports authored by Bonitas Research, a series of wrongdoings was brought to light. Primary areas of governance concerns include…

1. JinkoSolar’s Chairman Li looting billions of dollars through a corrupt personal acquisition wherein Chairman Li was allowed to purchase a JinkoSolar asset at a 40+% discount to market value.

2. Chairman Li’s brother benefits from controlling a key supplier within Jinko’s supply chain called Zhejiang Xinruixin Energy Co., Ltd. Xinruixin’s Chinese IPO prospectus documents reveal that >99% of revenue is derived from JinkoSolar. It is clear that Xinruixin’s business would not exist without the support from Jinko.

3. Blatant fraud has occurred through the overstatement of Australian solar module sales by US$209mm. There is a serious dichotomy between Jinko’s SEC filings and the local Australian ASIC filings, wherein the SEC filings reveal an overstatement of their Australian sales figures of US$209mm.

4. Understatement of liabilities by US$42mm that derive from the customs duties owed on the disposal of Jinko’s South African subsidiary. The South Africa Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (“CIPC”) details on the unknown acquirer of the subsidiary show an address change listed to 64 Kort Street, Parys, Free State. Upon sending an investigator to the location, nothing was found other than a wall of cheap textile products.

On the Daqo front, the CEO and board members have been involved with several stocks that have gone down (we have reached the part of the report where you get charts that go down). Daqo CEO Longgen Zhang was the director of a company called X Financial (XYF), a 2019 IPO of an online personal finance company in China. Interestingly, Mr. Zhang is also on the board of Jinko. Again, Jinko is Daqo’s second-largest customer.

Conclusion

Propelled by forced labor and sweetheart coal deals from an organization sanctioned for crimes against humanity, Daqo has ascended far beyond its origins as a tiny producer of a volatile commodity. It is one of the largest polysilicon producers in the world, and it’s the lowest cost producer, a feat we hope you understand now how it was achieved. Whether directly in its factories or in the coal plants controlled by the XPCC, Daqo has clearly benefited from the use of forced labor. Jinko has a prison on its corporate campus, and yet both of these companies have benefited from the proliferation of ESG investments. As global energy is focused on this region, we expect more bad outcomes and more bad headlines.

Disclosure: We Are Short Shares of Daqo New Energy Corp (NYSE: DQ) and JinkoSolar Holding Co., Ltd (NYSE: JKS)

Appendix:

The following images demonstrate a selection of Daqo and Jinko Solar Xinjiang facilities located within extremely close proximity to Uyghur concentration camps and/or prisons. For reader’s purposes, yellow pins designate a Daqo/Jinko facility location, red pins designate a Uyghur concentration camp, and green pins designate a Uyghur prison. We note that all facility locations are obtained utilizing Bloomberg Terminal’s MAP <GO> function. Additionally, all prison and concentration camp locations were identified by The East Turkistan National Awakening Movement (ETNAM), who released their data tranches in the form of a Google Earth KMZ format plugin. A download is available here for those interested.

Bleecker Street Research LLC Terms and Conditions

By downloading from or viewing material on this website you agree to the following Terms of Service. Use of Bleecker Street Research LLC’s research is at your own risk. In no event should Bleecker Street Research LLC or any Bleecker Street Research LLC Related Person (as defined hereunder) be liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information on this site. You further agree to do your own research and due diligence, consult your own financial, legal, and tax advisors before making any investment decision with respect to transacting in any securities of an issuer covered herein (a “Covered Issuer”).

As of the publication date of Bleecker Street Research LLC’S report, Bleecker Street Research LLC Related Persons (along with or through its members, partners, affiliates, employees, and/or Bleecker Street Research LLCs), clients, and investors, and/or their clients and investors have a short position in the securities of a Covered Issuer (and options, swaps, and other derivatives related to these securities), and therefore will realize significant gains in the event that the prices of a Covered Issuer’s securities decline. Bleecker Street Research LLC and Bleecker Street Research LLC Related Persons are likely to continue to transact in Covered Issuers’ securities for an indefinite period after an initial report on a Covered Issuer, and such position(s) may be long, short, or neutral at any time hereafter regardless of their initial position(s) and views as stated in the Bleecker Street Research LLC’S research. One or more Bleecker Street Research LLC Related Persons have provided Bleecker Street Research LLC with publicly available information that Bleecker Street Research LLC has included in this report, following Bleecker Street Research LLC’S independent due diligence.

Research is not investment advice nor a recommendation or solicitation to buy securities. To the best of Bleecker Street Research LLC’s ability and belief, all information contained herein is accurate and reliable, and has been obtained from public sources we believe to be accurate and reliable, and who are not insiders or connected persons of the securities of a Covered Issuer or who may otherwise owe any fiduciary duty or duty of confidentiality to the Covered Issuer. However, such information is presented “as is,” without warranty of any kind – whether express or implied. Bleecker Street Research LLC makes no representation, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, or completeness of any such information or with regard to the results to be obtained from its use. Research may contain forward-looking statements, estimates, projections, and opinions with respect to among other things, certain accounting, legal, and regulatory issues the issuer faces and the potential impact of those issues on its future business, financial condition, and results of operations, as well as more generally, the issuer’s anticipated operating performance, access to capital markets, market conditions, assets, and liabilities. Such statements, estimates, projections, and opinions may prove to be substantially inaccurate and are inherently subject to significant risks and uncertainties beyond Bleecker Street Research LLC’s control. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice, and Bleecker Street Research LLC does not undertake to update or supplement this report or any of the information contained herein. You agree that the information on this website is copyrighted, and you, therefore, agree not to distribute this information (whether the downloaded file, copies/images/reproductions, or the link to these files) in any manner other than by providing the following link: Bleecker Street Research LLC bleeckerstreetresearch.com The failure of Bleecker Street Research LLC to exercise or enforce any right or provision of these Terms of Service shall not constitute a waiver of this right or provision. If any provision of these Terms of Service is found by a court of competent jurisdiction to be invalid, the parties nevertheless agree that the court should endeavor to give effect to the parties intentions as reflected in the provision and rule that the other provisions of these Terms of Service remain in full force and effect, in particular as to this governing law and jurisdiction provision. You agree that regardless of any statute or law to the contrary, any claim or cause of action arising out of or related to the use of this website or the material herein must be filed within one (1) year after such claim or cause of action arose or be forever barred.

Bleecker Street Research LLC Related Person is defined as: Bleecker Street Research LLC and its affiliates and related parties, including, but not limited to, any principals, officers, directors, employees, members, clients, investors, Bleecker Street Research LLCs, and agents.